Creative Coding in 3 Steps: Squares

The square; four straight lines of equal length and four equal angles. What sounds like the most boring of the quadrilaterals has an almost magical aura. Think about the sides of a dice, the chessboard, or the floor area of the Egyptian pyramids. And in creative coding, too, the square makes for a formidable subject.

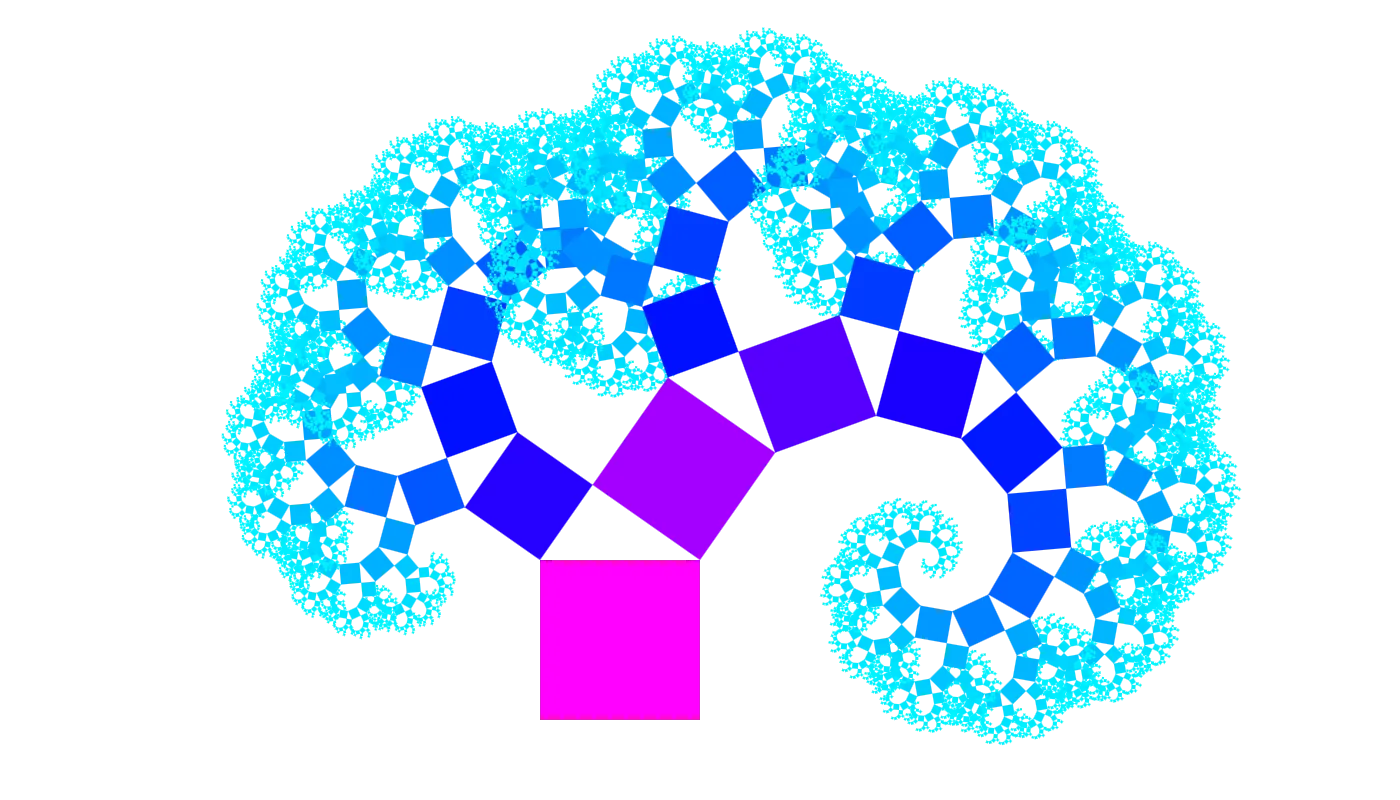

I would like to drive that point home by showing you an example of generative art that consists solely of squares and sadly did not make it into the zine: Hypnotic Squares by William J. Kolomyjec.

For me, creative coding means making art with computer code, algorithms, machines… any device that takes a bit of the process out of my hands.

The zine stands in the tradition of type-in programs inside computer magazines and books of the late 1970s to early 1990s: computer code meant to be entered via the keyboard by the reader. What sounds like a huge pain was sometimes the only way to transfer source code and knowledge. On the plus side, readers didn’t need a lot of prior knowledge and had the opportunity to learn as they typed.

Obviously, in times of the internet and smartphones this is not necessary anymore, but I would argue that typing in short code listings, misspelling commands, and fixing them is still a great way to get one’s feet wet when facing a new topic. Let’s draw our first square and use the mouse position on the canvas to steer size and rotation. Type in the following code at editor.p5js.org.

You don’t need an account, unless you want to save your work. The account is free and data collection is minimal.

let s = 100;

let a = 0;

function setup() {

createCanvas(400, 400);

rectMode(CENTER);

}

function draw() {

background(220);

translate(width/2, height/2);

rotate(a);

square(0, 0, s);

}

function mouseMoved() {

s = mouseX;

a = PI * mouseY / height;

}

Please note: These code snippets do ignore some best practices in programming, like meaningful names for variables and using whitespace to make operator use more readable, for reasons of space in the physical zine. I will provide a commented and hopefully more educating version soon.

We added interaction to our sketch! Interaction is a powerful tool that can turn observers into participants.

There are more inputs than mouse, think keyboard, microphone, web cam, touch gestures, gyroscope, … But let’s stick to the mouse and our one square for now. With just a few code changes, we can interactively draw on the canvas.

Type in the code and go nuts! You can clear the canvas with a left mouse click.

let s = 100;

let a = 0;

function setup() {

createCanvas(400, 400);

rectMode(CENTER);

noFill();

}

function draw() {

translate(width/2, height/2);

rotate(a);

square(0, 0, s);

}

function mouseMoved() {

s = mouseX;

a = PI * mouseY / height;

}

function mouseClicked() {

clear();

}

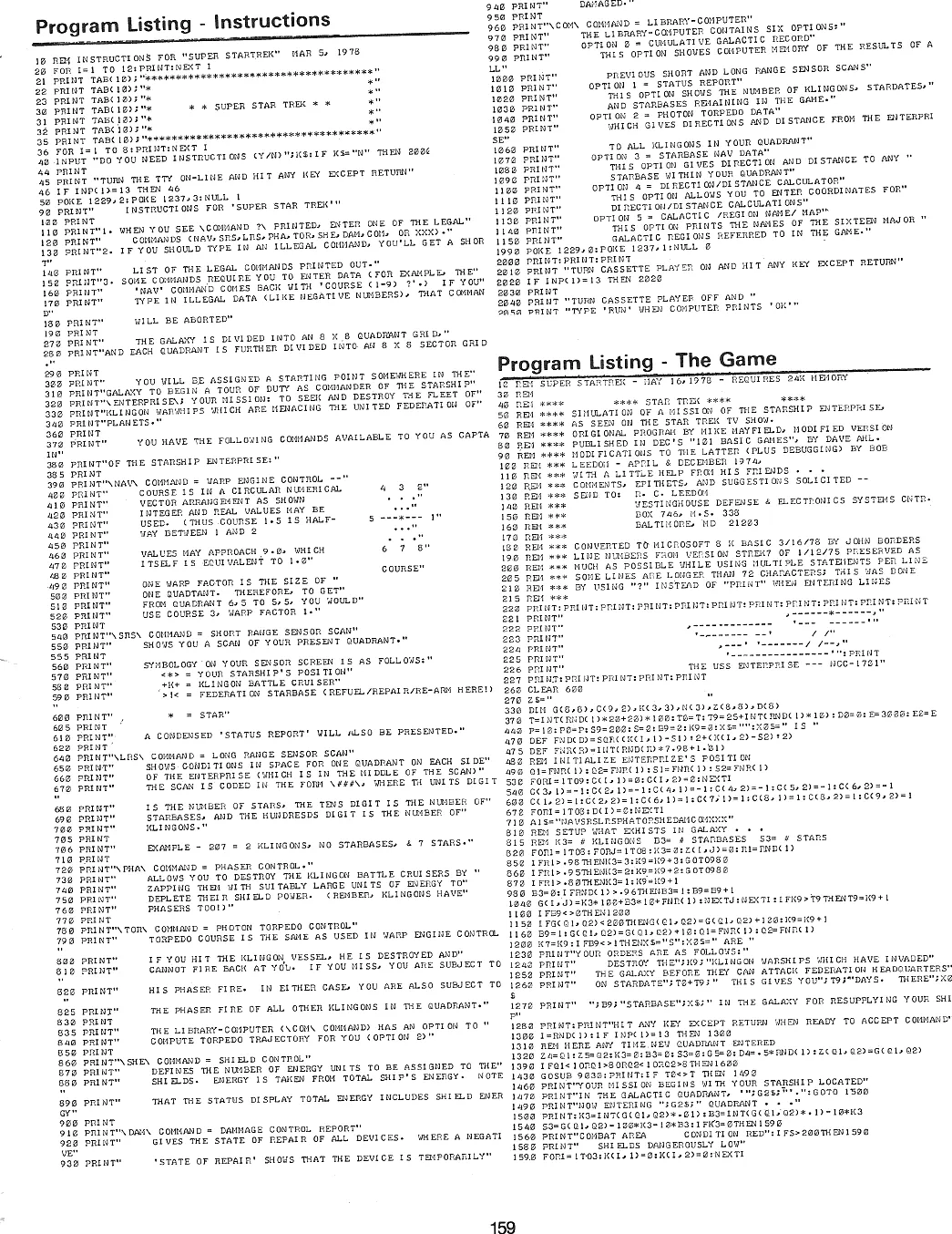

Result

What did you “draw” with one interactive square?

So far we just handled one square. Imagine what you could do with many squares!

“Many” sounds like repetition, iteration … or recursion: the concept of something being defined in terms of itself. Like the function fork down below, that includes calls to itself. Applied cleverly, recursion can lead to beautiful fractal geometries.

It is a lot of code, but I think it’s worth it to type or copy’n’paste it in. Not just because we bring back color :) Once done, change the value of variable a to 50. Then to 45. Can you image what happens when you change it to 20?!

const a = 55;

const s = 80;

function setup() {

createCanvas(700, 400);

angleMode(DEGREES);

colorMode(HSL);

noStroke();

fork(270, 280, s);

}

function fork(x, y, size) {

if (size < 1) return;

translate(x, y);

const h = lerp(

300, 180,

(s-size)/s

);

fill(h, 100, 50);

square(0, 0, size);

const s1 = size * cos(a);

const s2 = size * sin(a);

push();

rotate(-a);

fork(0, -s1, s1);

pop();

push();

rotate(90-a);

fork(0, -s1-s2, s2);

pop();

}

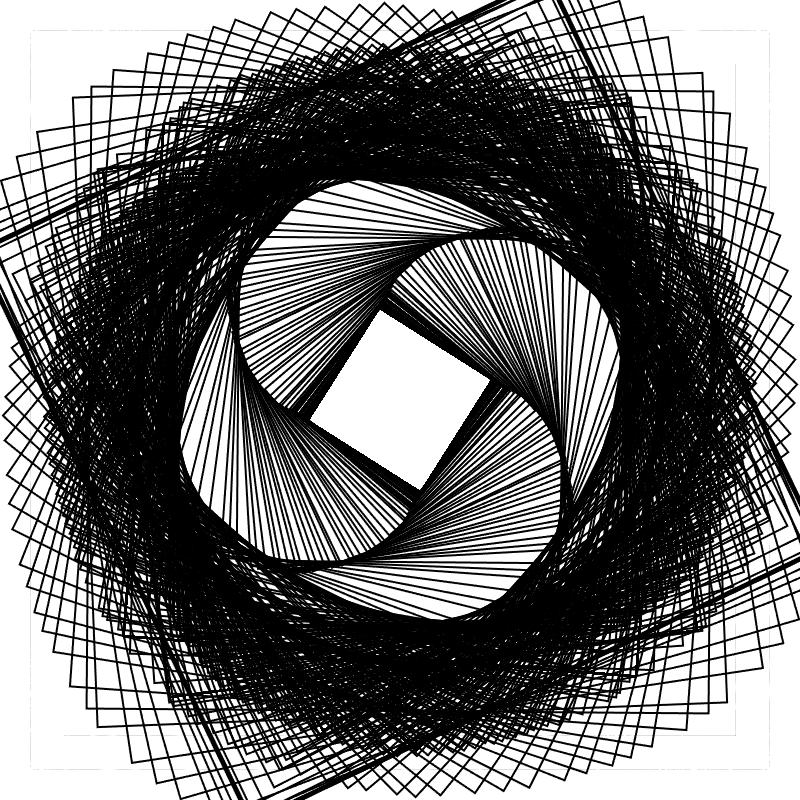

Result

What this code listing produces is called a Pythagoras Tree, which was invented by the Dutch math teacher—and friend of M.C. Escher—Albert E. Bosman. I was lucky enough to look at Bosman’s original work while visiting the Escher in Het Paleis museum in The Hague.

I hope you enjoyed this little creative coding adventure. You don’t have to stop here, though! Play around with the code, change stuff, break it, try to make it yours.

We have been using a tool called p5.js, a creative coding library written in the programming language JavaScript. p5.js is free and open-source and backed by a wonderful community. If you are looking to continue your creative coding journey, p5.js is a great place to start!

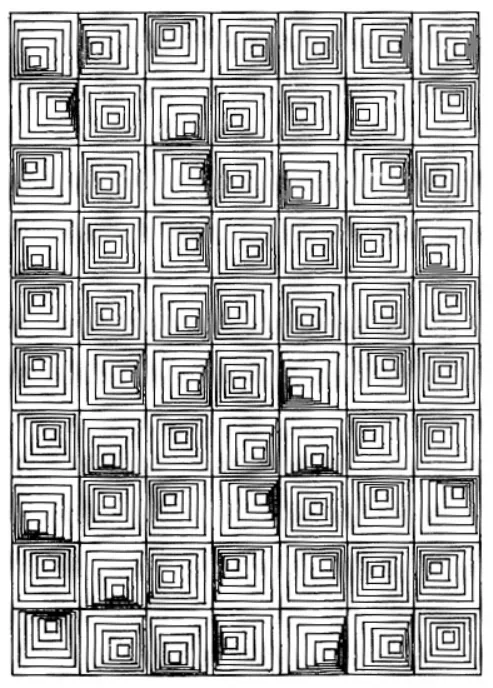

The Poster Inside the Zine and Why Each Zine Is Unique

The inside of the zine is my tribute to Schotter (German for “gravel”) by Georg Nees (1926–2016), a pioneer of computer and generative art. This work is also sometimes referred to as Würfel-Unordnung (English: Cubic Disarray) and covered by the tutorials of Generative Artistry.

Every zine is plotted with a unique version of this interpretation.

And with “plotted” I mean that every zine has been created with my AxiDraw SE/A3 pen plotter. Not only is every poster on the inside a unique vector graphic, but also every pen stroke and every letter is slightly different; a pen plotter is a very reliable machine, but two plots are still never 100% identical.

I like to think that the machine in my process adds a lot of character on its own to the final outcome.

The zine is unique. And so are you.